If you have a diversified portfolio, you might begin to second guess your target allocation when a piece—or maybe more than a piece—is not going in your favor. Should you have been more conservative? More Aggressive? Maybe you should have just bought the S&P 500 Index?

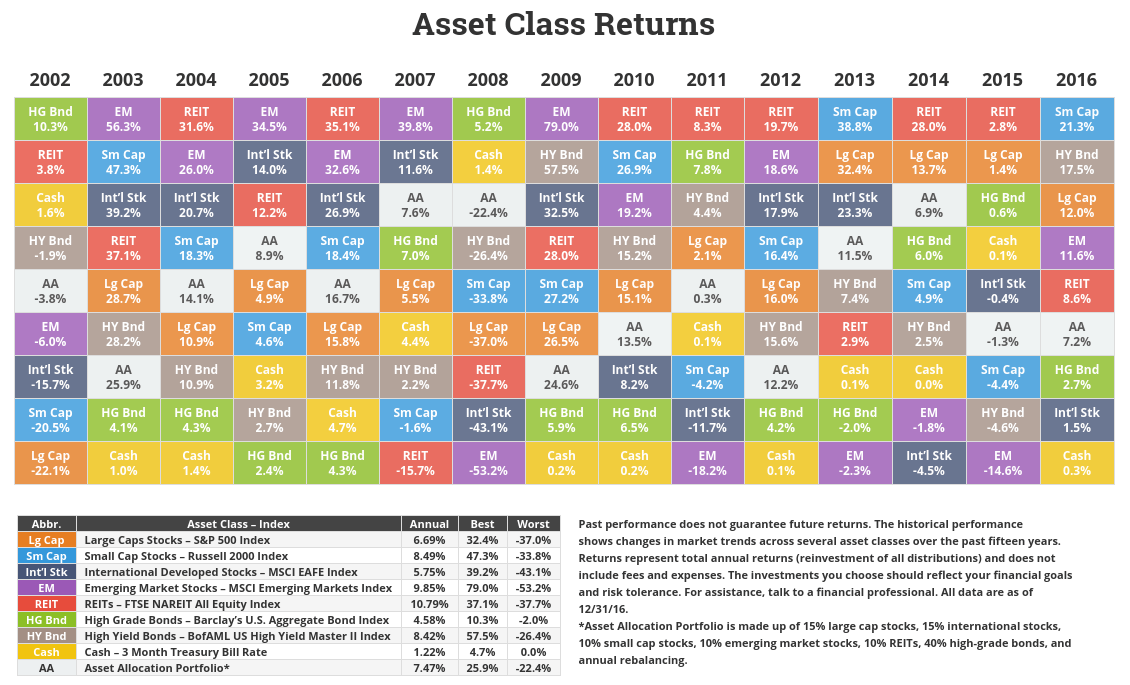

Regardless of what you believe you missed out on or could have avoided, asset classes, sectors, and individual stocks will perform in an unpredictable manner. Even while knowing this, you will be prone to love the top gainers and hate the laggards. And just when recency bias and regret creep in, these investments will move around in the performance pecking order and flip that love/hate script at the blink of an eye. Asset class return variability is as close to a sure bet that you will find in the markets. Take this chart for example:

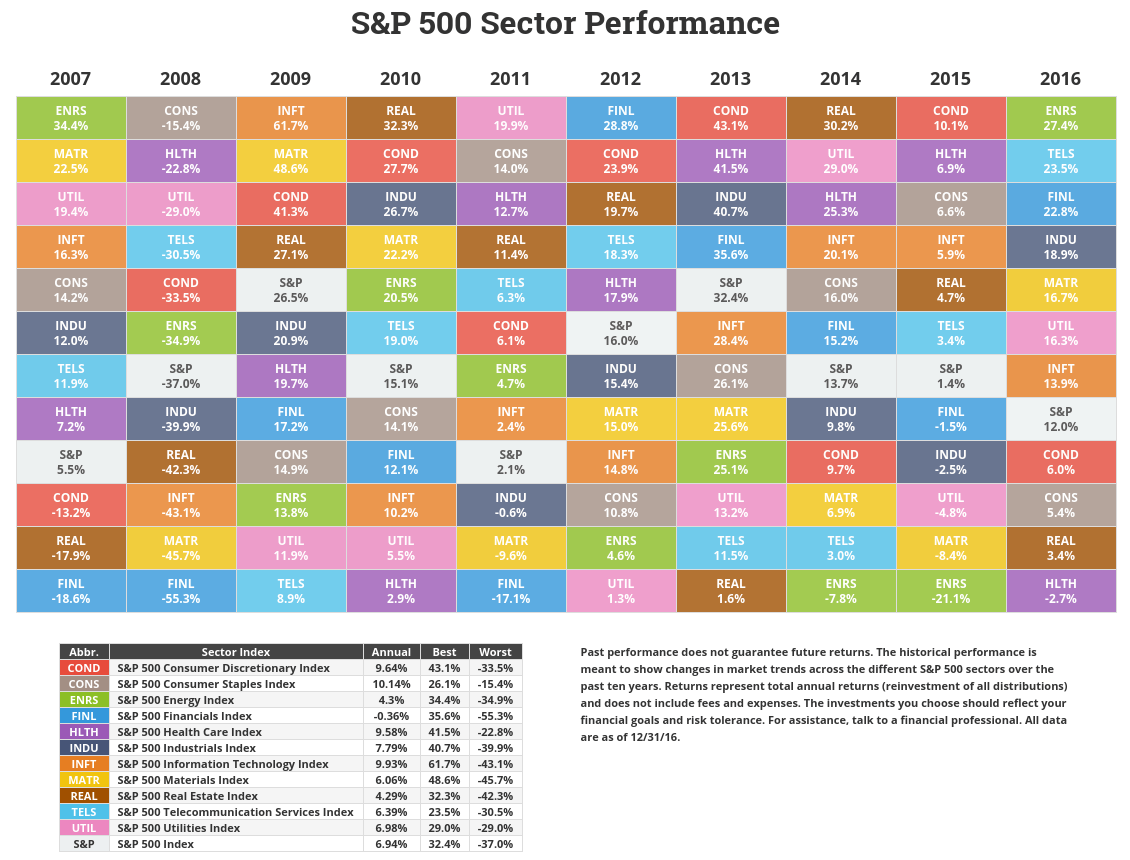

Now, let’s talk sectors. What about just buying the technology sector because of rapid and never-ending innovation or perhaps the energy sector because you are bullish on oil prices going higher? Not that simple either apparently:

Or maybe you are thinking of rolling the dice and making a concentrated bet on a few stocks or bonds. After all, those “FANG” stocks have been working out pretty well lately, and long-duration municipal bonds can provide tax-free income for years. While that may be true, you will still want to understand the risks involved. Here are just a few things to consider before you go all-in:

| Market risk: | Overall performance of the financial markets. |

| Business risk: | A company having lower than anticipated profits. |

| Liquidity risk: | An asset or security cannot be traded quickly enough without hurting its price. |

| Credit risk: | Default on a debt from failure to make a payment. |

| Inflation risk: | Purchasing power risk where money isn’t worth what previously anticipated. |

| Interest rate risk: | Investment values can change due to a rise or drop in rates. |

| Political risk: | Unfavorable change or instability in a country’s government. |

| Currency risk: | Exchange rates change. |

How do you compile, correlate, and quantify all of those risks? I know that I can’t do it. I had to use Google just to remember all of them.

So maybe none of this is relevant to you or it’s overkill? You are only buying the American economy because while it might not give you the best returns in a given year, it will always win out in the end. Warren Buffet said so. Just buy the S&P 500 or total US stock market, right? Yes, you are indeed probably right. I, myself, will likely own some form of a US index the rest of my life.

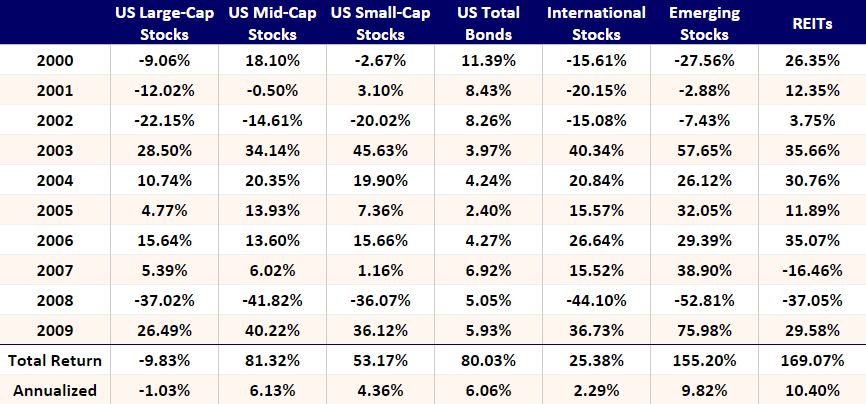

However, what if your years of market exposure do not allow for the S&P 500 to catch up for less than average gains. Underperformance can last for years—even decades. It certainly has happened before.

The Fat Pitch examined different holding periods dating back to 1900. One example that stood out was a what-if scenario with $100,000 invested in 1954 and held until 1984. For a frame of reference, the economy was booming in the 50s and 60s after World War II. The early 80s saw another bull market too. You would have made out well, right? Adjusted for inflation, your $100,000 would only be $120,000 a full 30 years later! That is an average real return of less than 1% per year.

Well, you might say that was a long time ago. Things change. But you know what—the 2000s weren’t so hot for large-cap US stocks either. To compare, here is how returns fared versus other asset classes:

And that’s before inflation.

You’d almost certainly make out better than the figures above by dollar-cost-averaging along the way if these were your working years, and the S&P 500 has obviously been back on track for a while now. But what if the years of poor performance are crucial post-retirement years and you are drawing from your portfolio along the way? You could be in trouble.

So the next time you find yourself second-guessing your diversified portfolio with a “shoulda, woulda, coulda,” take a step back and think about what you can actually control.

You can control having a plan. You can control knowing what you are invested in and why. You can control the fees that you pay. And you can control your diversification with an admission that you can’t predict the future.